He walked out alone — and refuses to let the story fade

Bill Spade still sees the stairwells. The dust. The weight of concrete pressing down. Twenty-four years after the Sept. 11 attacks, the FDNY firefighter from Staten Island carries a memory he didn’t ask for: he says he was the last firefighter to escape the North Tower before it collapsed. He was also the only member of Rescue 5 to make it home that day.

He had two small boys then — one not yet six, the other just two months old. In the chaos, as debris pinned him and the tower gave way, he prepared not to survive. He ran through their names in his head and made peace with the thought that his infant son would grow up without knowing his father. Then, against odds that still feel unreal, he found a path out.

What happened next hit even harder. When the calls finally came, the news was brutal and simple: the men he’d had breakfast with, the crew he trained and trusted, were gone. In a firehouse culture where the table is the center of the world, that kind of loss never stops echoing. In all, 343 FDNY firefighters died that day, part of a toll that claimed 2,977 lives.

Spade has told this story hundreds of times, but not to relive the worst day of his life. He tells it because of what happened in the years after. As his sons moved through New York City public schools, he kept asking: what did you learn about 9/11? The answer was usually the same — a moment of silence, maybe a sentence or two, then back to the regular schedule. For him, that wasn’t remembrance. It felt like erasure.

So he started showing up. Classrooms. Teacher trainings. Community rooms. He brings students into the stairwell with him, step by step, in plain language. He explains what gear weighed, how radios crackled, how firefighters split tasks and how fast plans had to change. He keeps it human, not cinematic. He watches the room go quiet when students realize how young the victims were — and how young the country still was on that morning.

Teaching the hard parts — and why it matters now

Spade’s push is part of a wider effort by survivors, first responders, and educators who worry the attacks are slipping into a blur of dates and hashtags for students born long after 2001. Nearly a third of Americans today weren’t alive when the towers fell. For many schools, September is a busy month — new classes, new routines — and 9/11 can become a brief ritual instead of a lesson plan.

Teachers say they face real constraints. Standards vary state to state. Younger grades need age-appropriate material and careful pacing. Some families worry the content could overwhelm kids who’ve never seen footage of that day. Administrators juggle time for civics, history, and testing. The result, too often, is silence at 8:46 a.m. and little else.

Spade doesn’t ask for graphic detail. He argues for context. Who worked inside those buildings? What did firefighters, police, paramedics, and office workers do for strangers they’d never met? How did people help each other get down 80 flights in the dark? What changed afterward — from airport security to community service — and what never should change, like the duty to show up when it counts?

He also talks about the long tail of 9/11 — the illnesses that came later. Many responders and survivors developed cancers and respiratory diseases tied to toxic exposure at Ground Zero and the surrounding neighborhoods. Tens of thousands are enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Program. Congress permanently authorized the Victim Compensation Fund in 2019, reflecting a national promise that care and support won’t expire with the news cycle.

In schools, Spade’s visits tend to unlock questions students don’t ask in textbooks. How did you decide to go back up the stairs when everyone else was going down? What did courage look like when nothing seemed survivable? What does survivor’s guilt feel like years later? He answers carefully. He tells them bravery isn’t the absence of fear but moving with it. He points to practical choices — communication, training, trust — that turned chaos into chance.

He also offers teachers a path to teach without sensationalizing. Start with the timeline of the morning. Explain the roles: dispatchers, building staff, EMTs, firefighters, police, air traffic controllers. Use primary accounts from people who were there, not just clips. Anchor the lesson locally — who from your town was affected, what memorials exist nearby, which civic groups still serve families and responders.

Spade’s own firehouse, Rescue 5 on Staten Island, became a symbol of both loss and continuity. After the attacks, bells tolled and names were etched into memorials, but the company kept taking calls, training new members, and showing up for the next emergency. That’s another lesson he brings to classrooms: remembrance isn’t passive. It’s work — the daily kind that rarely makes headlines.

For families who lost someone, the calendar never softens. Anniversaries cut in different ways: the first year is public and raw; the fifth, quieter but sharp; the tenth feels like history compressing into ceremony; the twentieth arrived with a flood of documentaries and speeches. By the twenty-fourth, memory competes with the churn of the present. That’s when stories tethered to real people matter most.

When Spade speaks, he avoids politics. He sticks to the ground-level view: the sound of a radio channel going still, the grit in the air, the weight of a name said out loud. He mentions the ordinary details that make that day relatable — coffee before the run, jokes around the table, the routes they knew by heart. Students lean in because it doesn’t sound scripted. It sounds lived.

He’s not alone. Other survivors and first responders are doing similar work — recording oral histories, guiding museum tours, lending artifacts to schools, and helping teachers build lessons that meet kids where they are. The 9/11 Memorial & Museum has free curricula aligned to different grades. Local departments often host assemblies or open houses every September. Libraries and historical societies collect community stories so the record isn’t only national, it’s also neighborhood-level.

Spade ends his talks with a simple ask. Remember the names. Understand the choices. Carry the lessons. He leaves students with a short list they can hold onto:

- Learn one person’s story from that day and share it with someone else.

- Thank a first responder in your community and ask about their work.

- Do a small act of service in someone’s honor on Sept. 11.

- Ask your school to devote real classroom time, not just a moment of silence.

That last point still drives him. A moment of silence matters, he says, but silence alone can’t teach. The next generation needs words, context, and space to ask hard questions. Without that, the memory fades into a date on a calendar, and the people who lived and died in those hours become outlines instead of humans.

The work is personal, and it’s urgent. The class that starts kindergarten this fall will graduate high school in the 2040s. By then, most eyewitnesses will be gone. The recordings will do their best, but living voices like Spade’s bridge the gap between history and experience. He’s determined to keep showing up until he can’t.

He knows what forgetting looks like. He’s seen how it creeps in when we get busy, when we cushion the hard parts, when we file events under “too painful” and move on. He also knows what remembering can do. It can turn a quiet room into a conversation about duty, courage, and care for strangers. It can push a school to expand its lesson plan. It can keep a promise made in dust and darkness: that the people who ran toward danger won’t be reduced to a footnote.

That’s the pledge he carries from a collapsed stairwell to a room full of teenagers. Keep the stories going. Make them specific. Pass them on. The 9/11 legacy depends on that, and on the people willing to show up — again and again — to tell what they saw and what it cost.

9/11 legacy: A Staten Island firefighter fights forgetting, one classroom at a time

9/11 legacy: A Staten Island firefighter fights forgetting, one classroom at a time

Trump Hosts Saudi Crown Prince as $1 Trillion Investment Pact Announced in Washington

Trump Hosts Saudi Crown Prince as $1 Trillion Investment Pact Announced in Washington

What is the difference between tourist and tourism?

What is the difference between tourist and tourism?

How do you ethically travel to Hawaii?

How do you ethically travel to Hawaii?

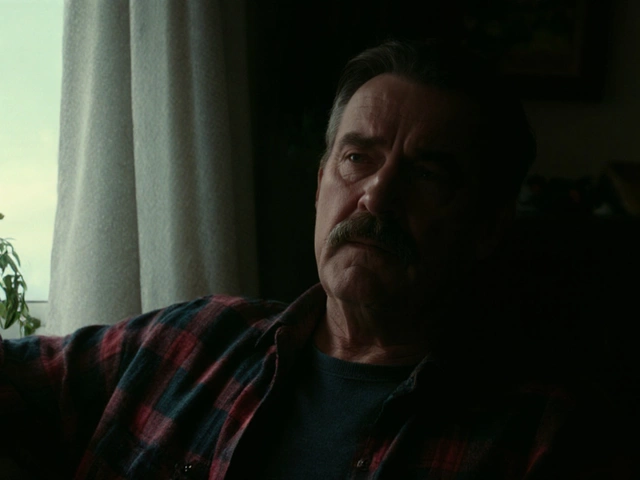

One Battle After Another: Prestige Film Poised for Box‑Office Miss

One Battle After Another: Prestige Film Poised for Box‑Office Miss